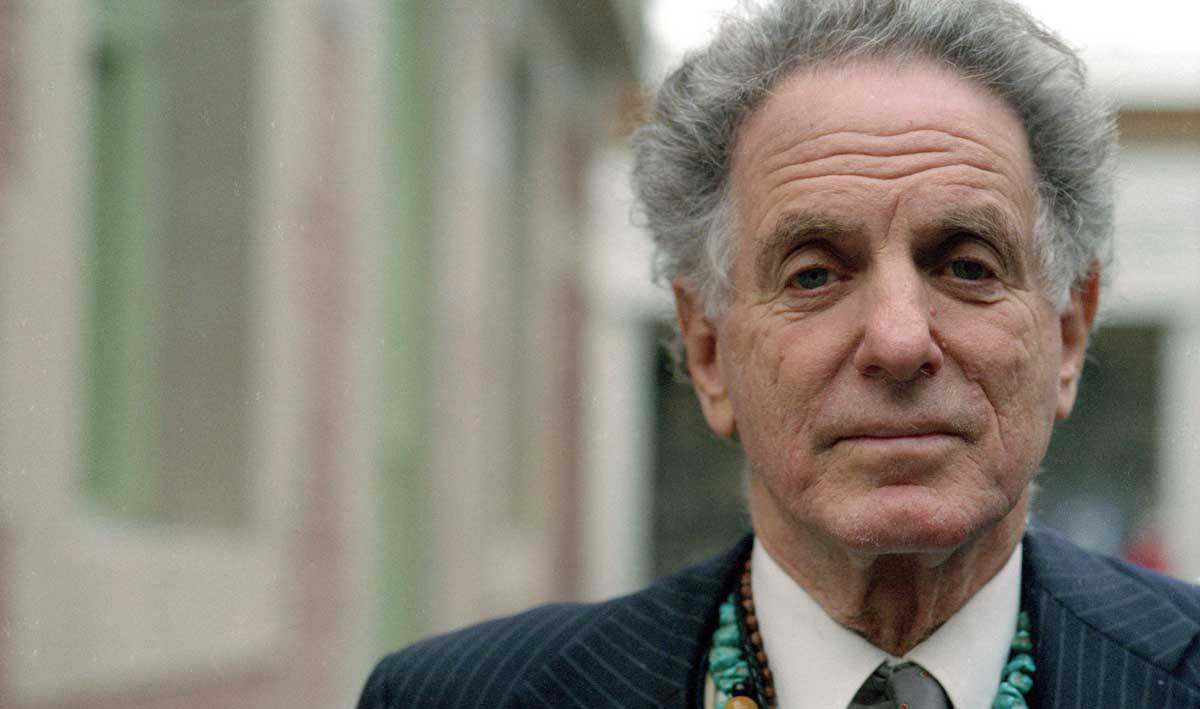

David Amram: A Father’s Lessons for a Storied Career

June 25, 2019

In our second installment of Fathers and Jewish Music, we interviewed composer David Amram about the impact that his father had on his life and career.

Starting in early childhood, the lessons that Philip Amram imparted to David came from a lifetime of hard work and service to the United States and its people; along with his ideals for the equality of mankind based in honoring each individual’s culture and heritage. Together, these built the foundation for a work ethic and world view that led not only to Mr. Amram’s well-earned success, but also the subject matter that fueled his curiosity and passion. These same qualities continue to sustain his active career at 88 years of age.

Read the full interview below, and share your own memories of Jewish music with your father.

Philip and Emily Amram, parents of composer David Amram, on their farm.

(Photo Courtesy of David Amram)

What was your father's profession when you were growing up?

My father had been to agricultural school and got a degree from Penn State University in agronomy, because he wanted to be a farmer. He worked for four years with my uncle doing just that in the 1920s, and we had a beautiful 160-acre farm. He loved doing it. Even back then, he realized that it was almost impossible to make a living farming at that point. Believe it or not, it was already difficult yet he continued to farm. He went to law school, which was unusual for someone in the 1920s to dare to do that, because usually, people went immediately as soon as they graduated from college.

He became a lawyer and worked with a firm in Philadelphia that wasn't that far from our farm, and also was a legal scholar and wrote a textbook called "Pennsylvania Procedure"—which is still used in schools today—and continued farming, which gave me a great work ethic. Then in 1942, he wanted to be in the army, which he'd been in World War I, to do something for the country, and was too old to be in combat and didn't want to go and do an office job. So he sold the farm. He went and he worked for the Department of Agriculture in the United States government, and was sent to New Caledonia to show people there principles of modern farming, since in New Caledonia, they had no source of food.

Then he was assigned—the Attorney General, head of the Justice Department was Francis Biddle, a Great Philadelphian—my father worked for him.

So we had moved from a 160-acre farm in 1942 to Washington, DC, and moved into what they called a “checkerboard neighborhood,” which was where African Americans and white folks all lived together in what was still segregated, because until 1952, basically it was south of the Mason-Dixon line.

So it was quite a change to move from 160-acre farm to a tiny place right next door to an all-night garage in a black and white neighborhood. It was terrific for me musically and socially to be part of that, to have done that; and both experiences remain a tremendous influence in my life.

What role, if any, did your father play in your development as a music artist?

Well, for one thing, he loved all kinds of music. Classical music from Europe. He used to try to play the piano reductions with the Brahms symphony, and I would hear him playing Brahms' first symphony on the piano reduction and spend an hour trying to get one or two measures together. Every time he would make a mistake, he'd swear, and then go back to where, like climbing a mountain, when you slip, you go back to where you slipped from and you try to go up another few feet before you slip back. I could hear him stumbling and fumbling, and that has still helped me enormously as a composer to realize that you can get it right, and it might take a long time, but if you did have an idea of what felt right, you could eventually arrive at the correct conclusion.

I realize that in a certain way, what my father tried to do, not just when he was playing the piano thinking I was asleep, but with everything—when we did farm work together or when I was practicing and playing the same thing 78 times—he would encourage me to do that, to say that practice makes perfect, and to be patient and to work hard, that you realize that there are no shortcuts. I think that's much more valuable for anybody to do, and I try to do with my kids.

I was very, very fortunate in the regard that rather than telling me how to have a great career and be a big winner, he explained to me that perhaps the course that I was taking was nearly hopeless and impossible, but if I loved it that much to try to do it anyway. If I couldn't survive, I could do the same thing he did as a farmer, which was to find other work, do that well, and still keep farming.

Since my father always dreamed of living on a kibbutz someday—but really wanted to stay in the United States—there was a certain way he felt that the farm, which he and his brother and father had, was almost like our own kibbutz. I was fortunate that, even though there were hardly any Jewish people there, we had Friday night services at home. My father brought all of that to us in our house, which was really a very important thing. I think a lot of people lose that sense of identity by feeling that they're marginalized or they're an outsider but that there's an inside group.

Then, by being where I was living during the Great Depression on a farm—since there was no real Jewish community except when our family and relatives would come to visit us—that this was something that you carry with you anyway, and that everyone else was kind of an outsider, too. On that level, it gave me a much better global perspective of what—not just Jewish people, but everybody—goes through.

Can you share a story about an experience with your father in which Jewish music played a part?

Well, he loved—as most people did in his youth and still do today, all these years later—the great cantor, Yossele Rosenblatt. I used to listen to his singing and it was just so incredibly beautiful. I felt something from that that really made me go way back in time to a place I had never been but felt that I was part of. This is way before I ever visited Israel or went around the world to other countries and found Jewish communities and Jewish people in all different kinds of places and felt that unconscious, tribal sense of bonding that is inexplicable… which you can't explain, and which scientists would say doesn't exist. We all know intellectually that Judaism is a religion. There's something else that's there, and you can feel it in the music, and you can see it in people's eyes and feel it with them.

When we would hear jazz and classical music, my father explained to me that these were both great forms of music and that European music was also a part at home in the United States, and all of our great Jewish musical traditions were also extremely valuable and also classical.

How did he feel about your decision to pursue a career in music?

When I was a little boy one time, I was up by my tractor. He said, “David, what would you really like to do when you grow up?” I said, “I'd like to be a farmer.” He said, “Well, that's impossible. You can't make a living doing that. I couldn't, even with my brother. You know how hard we work.” This is way back. He saw that it was already diminishing. The family farm was tough and in trouble, and that's years before I played Farm Aid, which I do. (They just gave me an award for 30 years of doing that.) And at that time, no one even used the phrase “family farmers.” That's essentially what it was, and everybody there was struggling.

David Amram milking a cow at his father and mother’s family farm in Feasterville Pennsylvania, 1937. (Photo Courtesy of David Amram)

So, he said, “That's impossible. What else?” I said, “I'd like to be a musician and a composer.” He said, “That's worse.” So in a certain sense, I realized that since I was stumbling and fumbling into what I hoped to do and didn't think it was beneath me to take any other kind of work in order to survive and somehow pay my rent, I decided that I would never have a career, because I was already following my career death wish. But I hoped someday that my music would have a career.

When I told that to my father, he kind of looked at me. He said, “Well, I guess I have a real mashugana for a son, but at least he is idealistic and has a goal.” He knew because I was a hard worker that I would find a way to survive whether I found another profession or worked part time as a manual laborer or did anything, that I would be able to survive. He was more interested, I think, in having me try to be a decent person than in being the first Jewish president of the United States.

Was there a time when your father was particularly proud of your work?

I think when the Philadelphia Orchestra played a piece called “Trail of Beauty,” which was based on Native American prayers and poems and traditional music. He came and he saw Eugene Ormandy with the Philadelphia Orchestra conduct my piece in Philadelphia.

Then he came to Washington—he still lived in Washington—and they played at the Kennedy Center, and some of his friends came to the concert. And by that time, that was 1977, I was already 46 years old. I think when people would say, “What does your son do?”… For those friends of his who were there, they could finally see some of what his son was doing.I think that made him feel proud and, hopefully, proud of himself because he was responsible for my having a good enough work ethic to be able to spend all those years where finally something wonderful like that would happen.

Amram composed and orchestrated the score for the film, "The Manchurian Candidate."

When I did the film scores for “Splendor in the Grass” and “The Manchurian Candidate,” that, of course, was something that everybody knew about. But I think he was most proud when he heard the Philadelphia Orchestra do that piece and when he heard—and when his friends could hear—my opera of the Holocaust, The Final Ingredient, because the 1965 one was broadcast nationally. There was no “Schindler's List” film then, and there was no general awareness that there even was a Holocaust, much less an opera being written about that that was shown on network television. That was a wonderful thing.

Which of your works or performances is or was his favorite?

I don't really know. I know he loved the opera, because there was one part when they were singing my setting of prayer Shema Yisroel and he said, “Boy, David. That sounds like that feeling that Yossele Rosenblatt had.”

I said, “I could hear a little of that even with the symphonic tenor and an orchestra and a setting when they were singing that. When they finally had the Passover celebration (based on a true story in a concentration camp, one prisoner got up and sang that) it was just glorious.”

I said, “Well, I was hoping to emulate some of the feeling.” It was the feeling that Yossele Rosenblatt had when he sang of bringing the past and the present into the same moment...

I suddenly flashed that it was because of him that I even went on the path to appreciate that. I think he had opened that door for me to find out who I was and who my family was and therefore was a better person because of that.

What is your father's legacy in your work as an artist?

Soloist Elmira Darvarova performs David Amram's Elegy for Violin and Orchestra with the composer conducting Carnegie Hall. January 28,20l9 (Photo courtesy of Chris Lee).

When I went to public school when we lived in Feasterville, there's a nearby place called Somerton, which was where the railroad station was, and then there was Feasterville, where I lived, where there were basically farms and a gas station across the street. Since I was the only Jewish kid in the school, and there were about five or six black kids, we would usually get beaten up or have to fight on the playground every day and get called all kinds of names.

But my father explained to me that since both the African American kids and I were routinely insulted and beaten up, that I wasn't the only person in the world who was judged by what was considered to be a label and a stereotype without having any idea that there was a person of that particular genre; and that the people who did that really didn't know any better because their parents and the society had trained them to think that way.

Secondly, most important, that I shouldn't think that way about myself, and I shouldn't think that way about any other person or any other people that I don't even know because of what their label is and what their so-called position is in society. Rather than running away from what I was told by my label I was supposed to be, I should learn more about it and embrace it.

So, he helped me to become aware that I should try to study the tradition of Judaism and all the amazing, accomplished Jewish people. So, when I would hear Ziggy Elman, the great jazz trumpet player on the radio, I would understand that he was a Jewish person who had embraced another culture and became a master of it.

Short documentary of David Amram's Milken Archive recording, Songs of the Soul. Amram discusses his multicultural inspirations and the great Yossele Rosenblatt.

Learn More About David Amram »

Share Your Story

Do you have a similar story to share? Was there a time when Jewish music played an important role in an experience with your father? We would love to hear from you! (We might even share your experiences on our social media channels.)