Tracks

Track |

Time |

Play |

| Part I - Kabbalat shabbat - Orchestral Prelude | 02:25 | |

| Part I - Kabbalat shabbat - Ma tovu | 03:39 | |

| Part I - Kabbalat shabbat - L'kha dodi | 03:26 | |

| Part I - Kabbalat shabbat - Tov l'hodot (Psalm 92) | 04:13 | |

| Part II - Arvit l'shabbat - Orchestral Prelude | 01:06 | |

| Part II - Arvit l'shabbat - The 23rd Psalm | 06:24 | |

| Part II - Arvit l'shabbat - Bar'khu | 01:14 | |

| Part II - Arvit l'shabbat - Ahavat olam | 02:50 | |

| Part II - Arvit l'shabbat - Sh'ma yisra'el | 01:44 | |

| Part II - Arvit l'shabbat - V'ahavta | 03:40 | |

| Part II - Arvit l'shabbat - Mi khamokha | 04:40 | |

| Part II - Arvit l'shabbat - Orchestal Interlude | 01:29 | |

| Part II - Arvit l'shabbat - V'sham'ru | 03:29 | |

| Part II - Arvit l'shabbat - Hashkivenu | 05:14 | |

| Part II - Arvit l'shabbat - Orchestral Interlude | 00:50 | |

| Part II - Arvit l'shabbat - Yih'yu l'ratzon | 01:56 | |

| Part II - Arvit l'shabbat - Kiddush | 03:34 | |

| Part III - Close of Service - Adoration | 01:46 | |

| Part III - Close of Service - Va'anahnu | 01:57 | |

| Part III - Close of Service - Orchestral Interlude | 01:47 | |

| Part III - Reader's Kaddish/Adon Olam | 08:52 | |

| Part III- Grant Us Peace/Benediction | 05:46 |

Liner Notes

Notwithstanding his many subsequent large-scale grand religious works, Berlinski always considered Avodat shabbat—his complete setting of the Reform version of the Friday evening Sabbath service according to the Union Prayer Book—his magnum opus. In some ways this work has come to represent a continuation of the path forged by Ernest Bloch and Darius Milhaud, who had successfully approached the Hebrew liturgy for the first time not only as specific synagogue music for worship, but also as universal artistic expression that could transcend practical Judaic and religious confines. Bloch and Milhaud had written Sabbath morning services, while Berlinski addressed the evening liturgy. And, whereas Bloch had used traditional material directly in only one part, and Milhaud had incorporated significant parts of the rare Provençal liturgical melodic tradition, Berlinski chose to rely, albeit not slavishly, on Ashkenazi prayer modes and biblical cantillation motifs.

Although Berlinski was consciously inspired by those two works—especially Bloch’s—his own service was not begun with such lofty aspirations. It began as synagogue music per se and developed later into the universal statement that it indeed is. Avodat shabbat was born as a commission by Cantor David Putterman for New York’s Park Avenue Synagogue as part of its extraordinary program of encouraging both highly established and promising composers to experiment with liturgical expression for its annual “new music” services. The timing in terms of Berlinski’s own development was fortuitous, since he had become increasingly disillusioned with the dearth of worthy artistic endeavor among many North American Reform synagogues and what he perceived to be a static, if not fossilized, condition. He was well aware of much worthy contemporary synagogue music as individual settings, but he saw little opportunity for a broader and deeper expression of the liturgy as cultivated art music. Apart from a few isolated incidents, Putterman’s annual commissions were providing the only real incentive for composers to devote their gifts to the synagogue on that level.

Cantor Putterman, generally conservative in his risks, and knowing that Berlinski had not yet explored the liturgy on that artistic level, invited him first to write a single setting for v’sham’ru, a brief text in the Friday evening service. After its premiere at the Park Avenue Synagogue, Putterman, now fully satisfied that Berlinski was a major talent, commissioned him to write a complete service. Avodat shabbat received its premiere in its original form (cantor, choir, and organ) at Park Avenue in 1958. Following that premiere, Berlinski’s friend Rabbi Abraham Klausner (congregation Emanu-El in Yonkers, New York) became convinced of its higher possibilities as a work for serious rendition within a symphonic context. In 1963, Rabbi Klausner showed the score to his friend Leonard Bernstein, who enthusiastically supported its public concert performance. Bernstein noted that he was especially impressed by its simplicity and its freshness: “from the heart... and a fine compromise between tradition and somewhat contemporary sounds.” He even wrote that he might consider performing the work himself in the future.

Armed with the Bernstein letter, Rabbi Klausner was able to persuade the Union of American Hebrew Congregations (the lay federation of American Reform congregations) to fund Berlinski’s orchestration of the work and the premiere of the new version. His orchestration was ambitious, perhaps even a bit overly so: double woodwinds plus English horn, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, two harps, strings, and elaborate percussion (cymbals; triangle; gong; tenor, bass, and small drums; and tambourine)—but, daringly, without violins. Berlinski also expanded the original solo vocal parts to include a soprano and mezzo-soprano or contralto, and he added settings for a few texts. This version was given its premiere that same year (1963) at Lincoln Center in New York, with the tenor role sung by Cantor Jacob Barkin, and the chorus and orchestra conducted by Abraham Kaplan. It shared the program with Leonard Bernstein’s Jeremiah Symphony.

Upon his acceptance of the original Park Avenue commission, Berlinski began by approaching the task according to his previously worked-out convictions concerning new sacred music: “There are three different elements that must be combined in the creation of a liturgical work,” he once wrote. “The spontaneous spark, without which a composer is not truly a composer; a clear understanding of the religious function of the music, without which a work will lack direction and conviction; and, finally, a knowledge of the traditional materials that are common denominators between the composer and the congregation.”

The harmonic structure often reflects the tension between the two basic traditional modes of the Ashkenazi Sabbath eve liturgy: the so-called adonai malakh mode, based on a scale akin to Western major but with important differences, including a scale that embraces more than an octave; and the magen avot mode, whose scale is akin to natural minor. In one instance (the l’kha dodi), there is the direct quotation of a specific traditional tune. Pervading the service is what the eminent synagogue composer Herbert Fromm called a “personal interpretation of tradition.”

Of the various devices and techniques that bring formal unity to Avodat shabbat and render it a cohesive work, none is so forceful and basic as the continuously recurring principal motive, derived from a fusion of biblical cantillation and traditional psalmody and introduced in the opening prelude. The prelude’s middle section generates the solo cantorial line in the ma tovu, a typical (but not liturgically required) introductory text for formal Reform as well as other nonorthodox Sabbath evening services. That motive appears throughout the ma tovu and, at the end, in the orchestra; and it recurs, both in its original statement and in varied or modified forms, almost in a rondo fashion, in the tov l’hodot; the bar’khu; the ahavat olam; toward the end of mi khamokha; near the conclusion of hashkivenu; and in the kiddush, Adoration, and closing Benediction. There are other, secondary recurring motives as well.

For his setting of l’kha dodi, Berlinski selected one of the oldest and most famous traditional Western, or “Amsterdam” Sephardi versions (often referred to as the Portuguese tradition in European and English sources). It must have been new, however, to typical American Ashkenazi congregations of that time, who undoubtedly thought it exotic. The tune has an interesting pedigree. Not only is its basic identity long established in the Amsterdam Sephardi tradition, but it is a firmly rooted l’kha dodi version in the London Portuguese Sephardi community as well—which is basically the same tradition despite local variances. This is hardly surprising, because many of the London Sephardi cantors came from Amsterdam over the years and became importers of such melodies. By the mid-19th century, this l’kha dodi was notated in a London compilation that reflected that Sephardi community’s established practice, which itself is a document of its authenticity. There are also other independently written and recorded confirmations of its long-established use in both London and Amsterdam, including one notation dating as far back as the late 18th century. There are, of course, local variances between the Amsterdam and London renditions that became crystallized as the tune was preserved in each community by oral transmission from one generation to the next; but it remains essentially the same tune. Moreover, the pioneer Jewish musicologist Abraham Zvi Idelsohn notated a variant of this tune in the early 20th century in Jerusalem as he heard it from a Moroccan Jew. The preeminent authority on Sephardi music, Edwin Seroussi, has therefore suggested Morocco as its origin, positing the thesis that it might well have been part of the North African Sephardi tradition that was exported to, and established in, Amsterdam and London in the 17th century.

Berlinski’s incorporation of a Sephardi tune into an otherwise fundamentally Ashkenazi-based service was not without aesthetic or historical justification. In the 19th century, certain solidly Ashkenazi German congregations, most notably in Hamburg, adopted a number of Portuguese Sephardi melodies into their repertoires and even came to consider them their own. In part, that practice stemmed, consciously or not, from a type of aristocratic pretension to perceived authenticity and, consequently, status. There is no evidence that this particular tune was included among those melodies. However, in 1877 Abraham Baer published his seminal and monumental compendium of the entire aggregate Ashkenazi synagogue melodic and modal tradition as he had heard it in numerous synagogues and from numerous cantors—lay as well as professional—throughout German-speaking Europe. (We do not know the extent to which, if any, his documentation reflected any actual firsthand experiences in eastern Europe.) He identified his entries according to their established tradition or practice—e.g., German (old or “new” version); general Ashkenazi; or “Polish” (i.e., eastern European, but probably as heard in Polish synagogues in Germany or the German cultural realm). For a number of tune entries in that compilation he also included alternative “Portuguese” versions—so labeled—that were generally known in the German Ashkenazi world. Among them is this l’kha dodi, which was Berlinski’s own source.

Berlinski used this tune audibly only for the refrain. His careful harmonization with well-chosen chromatic elements, far from masking it, actually adds a fresh parameter. He also demonstrated his solution here to the problem of finding a way to employ polyphony with an old monodic line while still preserving its character. There is a delicate counterpoint even in its initial statement, motivically derived from the spirit of the original tune, with a Milhaud-like countermelody heard in the orchestral introduction and then again at the conclusion. That refrain is modally altered for its second appearance to a quasi-minor variation, with a brief canonic gesture at the end. The third occurrence begins with a bit of canonic treatment; and the final return of the refrain is heard in its original form, tying it to the beginning.

In the cantorially sung strophes, however, Berlinski departed from the traditional version (in which the strophes would have been variations of the refrain) in favor of newly composed but modally oriented sustained lines. Here the cantor is given rhapsodic opportunities that flow nonetheless naturally back to the choral refrains.

In his setting of sh’ma yisra’el (including the v’ahavta, which is the continuation of that “credo” text, collectively known as the k’ri’at sh’ma), Berlinski clearly relied to advantage on his studies in biblical cantillation with Rosowski, one of the most significant authorities on the subject. Here, in the v’ahavta section, he creatively combines the Hebrew text for the cantor, who follows the authentic cantillation for that passage, responsorially with the choir in an unrelated and freer polyphony sung to the English translation in the Union Prayer Book. Its a cappella rendition reinforces the effect of antiquity, especially contrasted against the rich orchestration of much of the other music in the service. That conscious juxtaposition of two unrelated musical elements produces an arresting dialogue, especially at the end, when the choral part becomes melodically related to the cantillation—almost as a sort of resolution. Although bilingual rendition is not entirely unknown in certain Near Eastern Jewish traditions—for example, among Yemenite and other oriental Jewish practices (albeit employed sparingly for special texts)—it cannot be considered part of any Ashkenazi tradition. Berlinski’s fusion of Hebrew and English here must be viewed as an American innovation.

The hashkivenu is notable as the most pictorial expression of a dramatic text in this service. It faithfully represents the prayer’s sentiments and its progression from the opening pastoral mood toward a passionate climactic plea.

The adon olam, the most common closing hymn text for Sabbath and other holy day services, mirrors the decidedly Arabic meter of the poem as well as its strophic structure. But the music goes beyond its simple strophic nature (precise pattern repetition) to a complex one, where the second line of each two-line stanza is slightly and subtly varied. This creates an illusion of strophic repetition without monotony. The scheme is interrupted, however, in the fourth stanza, where the soprano line slowly approaches its climax chromatically. Although, unfortunately, the overall sophistication of Avodat shabbat, together with its difficulty, prevented its entry into the general synagogue repertoire, this adon olam did gain acceptance on its own in a number of synagogues during that time and received performances within regular services.

The entire Avodat shabbat is sung here in the Ashkenazi Hebrew pronunciation (including even the Sephardi l’kha dodi), since at that time it was still the overwhelmingly predominant pronunciation in virtually all Ashkenazi American synagogues. Berlinski therefore set all the texts to the particular consonant sounds and syllabic stresses of Ashkenazi Hebrew.

The press reviews of Avodat shabbat were largely enthusiastic, apart from one by Yiddish theater composer, Sholom Secunda, who could not relate to its complexity, its dissonant passages, its lack of more overtly traditional tunes, or even the very concept of it as a transcendent work of art. The Washington Post’s critic, on the other hand, found it “conservatively romantic,” texturally luxuriant, and exotic. Another critic was particularly struck by the cantorial line, which he interpreted as “flashing like a silver sword through the massed chorus.” Perhaps most telling was the observation of yet a third Washington critic, who remarked that Berlinski had not ignored the congregational role, noting that he “keeps it involved without descending to the trite or the obvious,” and that he succeeded in preserving an essential religious feeling throughout the work.

Lyrics

Sung in Hebrew and English

PART I. KABBALAT SHABBAT

ORCHESTRAL PRELUDE

MA TOVU

How lovely are your dwellings, O House of Israel. O Lord, through Your abundant kindness I enter Your house and worship You with reverence in Your holy sanctuary. I love Your presence in this place where Your glory resides. Here, I bow and worship before the Lord, my maker. And I pray to You, O Lord, that it shall be Your will to answer me with Your kindness and grace, and with the essence of Your truth that preserves us.

L'KHA DODI

REFRAIN:

Beloved, come—let us approach the Sabbath bride

And welcome the entrance of our Sabbath, the bride.

STROPHES 1, 3, and 9:

God, whose very uniqueness is His essence,

Whose very name is “One,”

Had us hear simultaneously the two imperatives

In His Sabbath commandments:

“Guard the Sabbath,” “Remember the Sabbath”—

Two words spoken at Sinai concurrently

Were heard by Israel as one command.

To our one and unique God, and to His name,

Let there be fame, glory, and praise.

Jerusalem, sanctuary of God the celestial King

And temporal capital of human kings,

Rise up from the midst of destruction and ruin.

Enough of your sitting in a valley of tears;

God’s great mercy awaits you—

Indeed His mercy awaits you!

Sabbath, you who are your Master’s crown,

Come in peace, in joy, in gladness

Into the midst of the faithful of a remarkably special people.

Come, O Sabbath bride—

Bride, come!

TOV L'HODOT (PSALM 92)

A Psalm. A song for the Sabbath day.

It is good to give thanks to the Lord, and to sing praises to Your name, Most High One,

To tell of Your kindness in the morning, to tell of Your faithfulness each night.

With a ten-stringed instrument and a nevel, with sacred thoughts sounded on the kinor.

For You, Lord, have brought me much gladness with Your works.

Let me revel in Your handiwork.

How great are Your works, Lord!

Your thoughts are indeed profound.

The ignorant do not know of this, nor can fools understand this: that though the wicked may spring up like grass;

And though evildoers may flourish, they do so only eventually to be destroyed forever.

But You, Lord, are to be exalted forever.

Here are Your enemies; Your enemies shall perish; the workers of evil shall be scattered.

You have elevated me to a place of high distinction, like the wild ox of old.

I am anointed with fresh and fragrant oil.

I have already seen the defeat of my foes;

I have already heard of the doom of the evil who plot and rise against me.

The righteous shall flourish like a palm tree, growing mighty as a cedar in Lebanon.

Planted in the Lord’s house, they shall flourish in the courtyard of our God.

They shall bear fruit even in old age, and be full of life’s vigor and freshness—

To declare that the Lord is upright and just, my Rock in Whom there is no unrighteousness.

PART II. ARVIT L'SHABBAT

ORCHESTRAL PRELUDE

THE 23rd PSALM

Sung in English

The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want.

He maketh me to lie down in green pastures;

He leadeth me beside the still waters.

He restoreth my soul;

He guideth me in straight paths for His name’s sake.

Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death,

I will fear no evil,

For Thou art with me;

Thy rod and Thy staff, they comfort me.

Thou preparest a table before me in the presence of mine enemies;

Thou hast anointed my head with oil; my cup runneth over.

Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life;

And I shall dwell in the house of the LORD forever.

BAR'KHU

Praise the Lord, to whom all praise is due.

Praised be the Lord, who is to be praised for all eternity.

Amen.

AHAVAT OLAM

You have loved the House of Israel, Your people, with an abiding love—teaching us Your Torah and commandments, Your statutes and judgments. Therefore, upon our retiring for the night and upon our arising, we will contemplate Your teachings and rejoice for all time in the words of Your Torah and its commandments. For they are the essence of our life and the length of our days. We will meditate on them day and night. May Your love never leave us. Praised be You, O Lord (praised be He and praised be His name) who loves His people Israel. Amen.

SH'MA YISRA'EL

Listen, Israel! The Lord is our God.

The Lord is the only God—His unity is His essence.

Praised and honored be the very name of His kingdom forever and ever.

V'AHAVTA

Sung in Hebrew and English

Thou shalt love the lord thy God with all thy heart, with all thy soul, and with all thy might. And these words which I command thee this day shall be in thy heart. Thou shalt teach them diligently unto thy children, speaking of them when thou sittest in thy house, when thou walkest by the way, when thou liest down, when thou risest up. And thou shalt bind them for a sign upon thy hand, and they shall be for frontlets between thine eyes. And thou shalt write them upon the doorposts of thy house and upon thy gates.

MI KHAMOKHA

Who, among all the mighty, can be compared with You, O Lord?

Who is like You, glorious in Your holiness,

Awesome beyond praise, performing wonders?

When You rescued the Israelites at the Sea of Reeds,

Splitting the sea in front of Moses,

Your children beheld Your majestic supreme power

And exclaimed: “This is our God: The Lord will reign for all time.”

ORCHESTRAL INTERLUDE

V'SHAM'RU

The children of Israel shall keep and guard the Sabbath and observe it throughout their generations as an eternal covenant. It is a sign between Me and the children of Israel forever, that the Lord created heaven and earth in six days, and that on the seventh day He rested and was refreshed.

HASHKIVENU

Cause us, O Lord, our God, to retire for the evening in peace

And then again to arise unto life, O our King,

And spread Your canopy of peace over us,

Direct us with Your counsel and save us for the sake of Your name. Be a shield around us.

Remove from our midst all enemies, plague, sword,

Violence, famine, hunger, and sorrow.

And also remove evil temptation from all around us,

Sheltering us in the shadow of your protecting wings.

For indeed You are a gracious and compassionate King.

Guard our going and coming, for life and in peace,

From now on and always spread over us

The sheltering canopy of Your peace.

Praised be You, O Lord

(praised be He and praised be His name),

Who spreads the canopy of peace over us

And over all Your people Israel, and over all Jerusalem.

Amen.

ORCHESTRAL INTERLUDE

YIH'YU L'RATZON

May my prayers of [articulated] words as well as the meditations of my heart be acceptable to You, Lord, my Rock and Redeemer.

KIDDUSH

Praised be You, Lord (praised be He and praised be His name), our God, King of the universe, who has created the fruit of the vine. Amen.

Praised be You, O Lord (praised be He and praised be His name), our God, King of the universe, Who has sanctified us through His commandments And has taken delight in us. Out of love and with favor You have given us the Holy Sabbath as a heritage, In remembrance of Your creation. For that first of our sacred days Recalls our exodus and liberation from Egypt. You chose us from among all Your peoples, And in Your love and favor made us holy By giving us the Holy Sabbath as a joyous heritage. Praised are You, O Lord, our God (praised be He and praised be His name), who hallows the Sabbath. Amen.

PART III. CLOSE OF SERVICE

ADORATION

Recited in English

Let us adore the ever living God and render praise unto Him, who spread out the heavens and established the earth, whose glory is revealed in the heavens above, and whose Greatness is manifest throughout the world. He is our God, and there is none else.

VANAḤNU

We bow the head in reverence and worship the King of Kings, the Holy One, praised be He.

ORCHESTRAL INTERLUDE

READER'S KADDISH

May God’s great name be even more exalted (amen) and sanctified in the world that He created according to His own will; and may He fully establish His kingdom in your lifetime, in your own days, and in the life of all those of the House of Israel— soon, indeed without delay.

Those praying here signal assent and say “amen.”

May His great name be praised forever, for all time, for all eternity.

Blessed, praised, glorified, exalted, elevated, adored, uplifted, and acclaimed be the name of the Holy One, blessed be He— over and beyond all the words of blessing and song, praise and consolation ever before uttered in this world. Those praying here signal assent and say “amen.”

May there be abundant peace for us and for all Israel; and those praying here signal assent and say “amen.”

May He who establishes peace in His high place establish peace for us and for all Israel; and those praying here signal assent and say “amen.”

ADON OLAM

Lord of the world, who reigned even before form was created,

At the time when His will brought everything into existence,

Then His name was proclaimed King.

And even should existence itself come to an end,

He, the Awesome One, would still reign alone.

He was, He is, He shall always remain in splendor throughout eternity.

He is “One”—there is not second or other to be compared with Him.

He is without beginning and without end;

All power and dominion are His.

He is my God and my ever living redeemer,

And the rock upon whom I rely in time of distress and sorrow.

He is my banner and my refuge,

The “portion in my cup”—my cup of life

Whenever I call to Him.

I entrust my spirit unto His hand

As I go to sleep and as I awake;

And my body will remain with my spirit.

The Lord is with me: I fear not.

GRANT US PEACE

Sung in English

Grant us peace, Thou eternal source of peace

Grant us peace, Thy most precious gift

O Thou eternal giver of peace

Bless all mankind with peace

O Thou eternal source of peace

Praised be Thou giver of peace

BENEDICTION

Sung in Hebrew and English

May the Lord bless thee and keep thee. Amen.

May the Lord let His countenance shine upon thee and be gracious unto thee. Amen.

May the Lord lift up His countenance upon thee and grant thee peace. Amen.

Credits

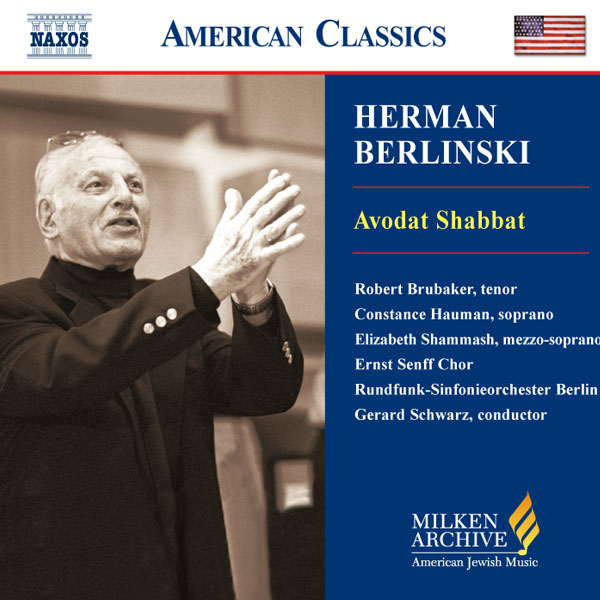

Composer: Herman BerlinskiPerformers: Robert Brubaker, Tenor; Ernst Senff Choir; Constance Hauman, Soprano; Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin; Gerard Schwarz, Conductor; Elizabeth Shammash, Mezzo-soprano

Publisher: Herman Berlinski Editions

Co-production with DeutschlandRadio and the ROC Berlin-GmbH

Translation from the Hebrew by Rabbi Morton M. Leifman