Orchestral Works of Jewish Spirit

From the curator

A symphony must be like the world, it must embrace everything.

—Gustav Mahler

The symphony is the sine qua non of Western classical music. A form that dates to the early 18th century, it has been subjected to myriad variations and metamorphoses without losing either its identity or its status as the yardstick by which nearly every composer is ultimately measured. The body of work that has emerged from this long tradition is the life-blood of orchestral ensembles the world over.

In the world of Jewish music, the typical performance context—by virtue of venue size or access to funding—cannot generally accommodate a full symphony orchestra. So while a number of symphonic works of Jewish content or character have been composed, and perhaps performed once or twice, few have gained sufficient prominence to join the standard repertoire that is performed by contemporary symphony orchestras.

So it is not surprising to read Neil W. Levin’s introduction to this volume and learn that the existence of a substantial body of symphonic Jewish music was a revelation, both to the members of the Milken Archive Editorial Board and to most of the conductors who participated in the recordings. As he writes, "we found that often even the most seasoned and conversant conductors, as well as aficionados of serious contemporary music, were almost completely unaware of this Jewish classical repertoire."

Symphonic Visions, which takes its name from a Herman Berlinski work, includes a full ten albums of symphonies, tone poems, orchestral suites, and concertos based on Jewish musical themes or programmatic topics. Collectively, they embrace a range of forms, styles, and artistic approaches.

Among the formal symphonies here are David Amram’s Symphony: Songs of the Soul, which draws on Jewish folk musics from around the world, Leonard Bernstein’s famous and highly personal Kaddish Symphony (No. 3), and Hugo Weisgall’s T’kiatot: Rituals for Rosh Hashana, based on the shofar blasts traditionally performed on the Jewish new year. The shofar blasts in T'kiatot serve, much as they do in their sacred context, as punctuating elements, or calls to spiritual awakening. But within the frame of this work’s dense and craggy texture they have a somewhat counterintuitive calming effect.

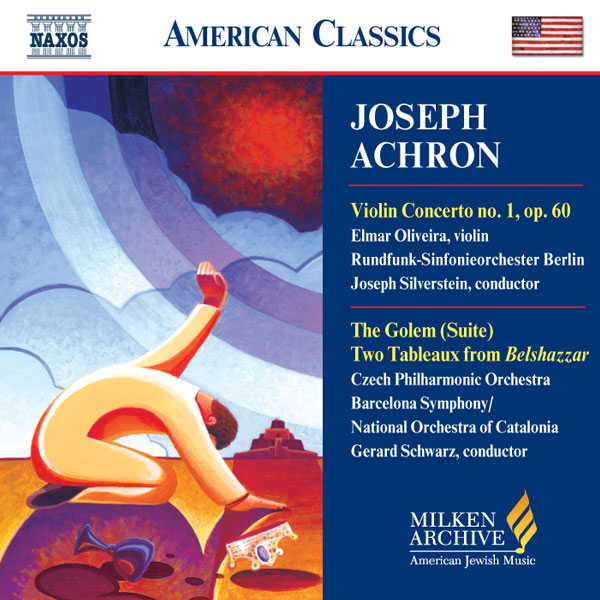

Concertos include Paul Schoenfield’s Concerto for Viola and Orchestra, which highlights its composer’s Bartókian use of folk elements; Joseph Achron’s Violin Concerto No. 1, based on biblical cantillation motifs; and an unpublished "Fantasy" by Sholom Secunda based specifically on biblical cantillations reserved in Ashkenazi custom for the High Holy Days. Discovered in manuscript form amongst the composer’s papers, it was reconstructed for the Milken Archive by Samuel Adler, whose Symphony No. 5: We Are the Echoes also appears here.

Orchestral tone poems by Aaron Avshalomov, Ernst Toch, and William Schuman explore key biblical episodes and characters. Avshalomov’s Four Bilblical Tableaux focuses on Esther, Ruth, Naomi, and Rebecca, and reflects the Siberian composer’s interest in Chinese musics. Judith is the main character in Schuman’s "choreographic poem," while Toch’s "rhapsodic poem" is based on the story of Jephta.

If few symphonies could truly be said to embrace the world, then assessing any body of work according to Mahler’s criterion would be unfair. The works in Symphonic Visions are nonetheless a reflection of a world, one in which the convergence of freedom and diaspora has opened doors to remarkable artistic achievement.

—Jeff Janeczko